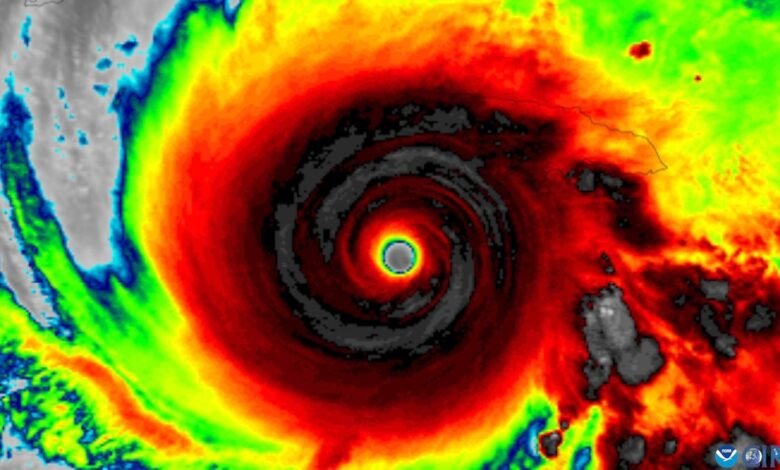

When Hurricane Melissa slammed into Jamaica on October 28, it showed just how devastatingly powerful a Category 5 hurricane can be—and then some.

It will be weeks before experts can truly assess just how badly Hurricane Melissa ravaged Jamaica and nearby islands. But scientists are already confident that climate change contributed to the storm’s horrifying strength, which sent winds gusting far beyond the minimum required for a Category 5. And Melissa could revive discussions swirling around whether the five categories of the Saffir-Simpson Hurricane Wind Scale are sufficient to describe the monstrous storms that climate change can fuel.

READ MORE: How Hurricane Melissa Became One of the Most Intense Atlantic Storms on Record

SEE MORE: Hurricane Melissa Images Reveal a Monster Storm for the Record Books

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

What would a Category 6 storm look like?

The Saffir-Simpson scale breaks hurricanes into numbered categories based solely on peak sustained wind speeds. By this scale, a storm with sustained maximum winds of 74 to 95 miles per hour is a Category 1 hurricane. When a storm’s winds hit 111 mph, it becomes Category 3, which also marks the official designation of a “major hurricane.” The most severe classification under the Saffir-Simpson scale, Category 5, marks hurricanes with sustained peak wind speeds of 157 mph or higher.

But last year hurricane scientists suggested that this “open-ended” nature of the Saffir-Simpson scale is no longer sufficient to convey the reality of modern hurricanes. They proposed the establishment of Category 6, which would begin at peak sustained wind speeds of 192 miles per hour.

As the researchers noted, so far, five storms reached this horrifying milestone, and all of them did so in years after 2010. Those storms were Hurricane Patricia in the eastern Pacific Ocean and four typhoons—which are not traditionally assigned categories—in the western Pacific: Haiyan, Goni, Meranti and Surigae.

Hurricane Melissa didn’t quite meet the proposed Category 6 boundary, with initial measurements suggesting maximum sustained wind speeds of 185 mph. That leaves it tied with several other serious storms—the “Labor Day” hurricane of 1935 and Hurricanes Gilbert, Wilma and Dorian in 1988, 2005 and 2019, respectively—for the second strongest peak sustained wind speed in the Atlantic Ocean.

The strongest sustained wind speed in the Atlantic on record occurred in 1980’s Hurricane Allen, which hit 190 mph, nearly grazing the researchers’ suggested Category 6.

Some scientists argue that extending the Saffir-Simpson scale is unnecessary, however. That argument rests on the fact that the scale includes not just category numbers and wind speeds but also notes about what kind of damage to expect from those winds. Indeed, Herbert Saffir, one of the scientists behind the scale, was a structural engineer who focused on wind damage.

Category 3 is described by the National Hurricane Center as causing “devastating damage,” with even well-built homes being vulnerable to losing their roof and the affected region facing a potentially days-long loss of water and electrical service. Both Categories 4 and 5 are described as causing “catastrophic damage”: “Most of the area will be uninhabitable for weeks or months,” the rubric reads. At that point, Category 6 opponents argue, there’s little further distinction to be made about just how dire the situation will be.

And some are concerned that an additional category could have the opposite effect of the one intended. “It could inflate the scale such that life-shattering storms assigned lower categories would garner even less attention than they already do,” wrote University of Arizona atmospheric scientist Kim Wood on Bluesky.

Climate change and monster storms

Hurricane Allen’s shocking winds in 1980, before a noticeable trend of increasingly intense hurricanes was observed, are an important reminder that climate change does not directly cause monster hurricanes. Scientists prefer to describe climate change as “loading the dice” for, or contributing to, the strength of serious storms.

And scientists have already concluded that climate change did indeed contribute to the strength of Hurricane Melissa. An analysis by the nonprofit research organization Climate Central calculated that the waters Melissa traveled over as a Category 5 storm as it approached Jamaica were more than one full degree Celsius (two full degrees Fahrenheit) hotter than normal—a circumstance that climate change made more than 700 times more likely.

A second rapid analysis, this one conducted by the organization ClimaMeter, determined that climate change strengthened Melissa’s winds and rain by about 10 percent compared with how the storm might have played out under conditions where humans had not added heat-trapping greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. Researchers will release other, similar “attribution analyses,” as these studies are known, in the coming days and weeks.

In general, however, scientists know that hurricanes are becoming more severe as climate change accelerates. Warmer ocean water fuels stronger winds, and warmer air holds more water, which can then become rainfall. Meanwhile rising sea levels make coastal regions more vulnerable to storm surge. Studies have shown that as climate change continues, a higher proportion of hurricanes are reaching Category 3, while other evidence shows that even tropical storms and weak hurricanes are intensifying as well.

But the initial analyses also point to a weakness of the Category 6 idea and an inherent weakness of the Saffir-Simpson scale as a risk communications tool: the scale considers only wind speeds, but hurricanes’ storm surge and rainfall can be just as hazardous, if not more so.

READ MORE: Hurricane Categories Don’t Capture All of a Storm’s True Dangers

Many of the most damaging storms of recent years caused unspeakable devastation while being far weaker than Category 5. Consider 2005’s Hurricane Katrina, which made landfall as a Category 3 storm but triggered enormous storm surge and killed more than 1,800 people. More recently, 2017’s Hurricane Harvey made landfall as a Category 4 storm, yet its most dangerous hazard was torrential rain, not wind.

Hurricane scientists have long been frustrated by the constraints and shortcomings of the Saffir-Simpson scale as a communications tool for the general public, and many are searching for a different metric that would be as easy for people to understand but would better incorporate the complex threats of any given storm.

That’s a tall order. “It’s impossible to boil the threats of a hurricane down to one number,” said Brian McNoldy, a hurricane researcher at the University of Miami, to Scientific American at the beginning of last year’s hurricane season.

The difficult truth is that hurricanes are complex beasts, inherently difficult to boil down into a single number. Hurricane Melissa’s devastation is the awful alchemy created by the unique combination of unstoppable gusts, seawater that is forced inland and deluge that pours out of the sky, all interacting with the landscape and human lives the storm found in its path.

Source link