The new PBS series “Black and Jewish America: An Interwoven History” may be a bitter pill to swallow for Jews steeped in stories of Jewish freedom riders, Jewish co-founders of the NAACP, and Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel marching with the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

According to the four-part documentary, which released its third episode Tuesday and is available to stream on pbs.org, the story of Blacks and Jews in the United States is much more complicated.

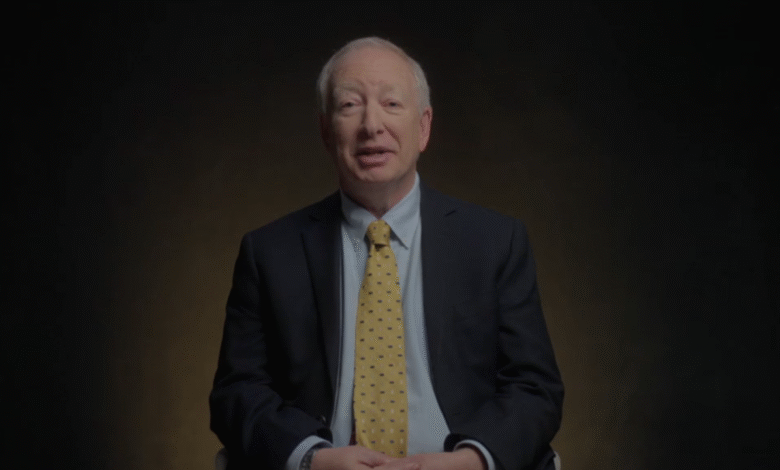

Marc Dollinger, a Jewish studies professor at San Francisco State University and author of “Black Power, Jewish Politics: Reinventing the Alliance in the 1960s,” puts it succinctly near the end of the second episode.

“American Jewish history has been a history of rapid social mobility. African American history has been a history of enslavement and institutional racism,” Dollinger tells viewers, before posing this question: “At what point in the alliance are those historical differences going to be seen?”

Topics the show has covered so far include Jewish and Black cooperation on elements of American pop culture in the early and mid-20th century, with a realistic and clear-eyed view allowing for the celebration of Jewish record producers who brought Black music to mass audiences — while leaving room to criticize them for underhanded financial deals with the musicians they championed.

World War II is likewise examined. In one segment, a Black veteran of WWII tells of his shock and horror at what he encountered when he helped liberate a Nazi death camp. But upon return to America, Black soldiers were not greeted with the same privileges as white soldiers of any faith. Says Gates in a voiceover, “When Jewish soldiers returned home, they were afforded honors and benefits in equal measure to their white counterparts. But it was a different story for their fellow Black veterans.”

Dollinger concurs onscreen, “If you were a white Jewish family, and your soldier returned from the war, the government is going to make it possible for you to get a house, go to college and start your business, which is an extraordinary recipe for upward social mobility.” But it wasn’t the same for Black veterans and their families. “For the African American community, it did not work out so nicely,” Dollinger says.

When producers emailed him, seeking an interview, Dollinger told J. his response was “hell yes!”

Dollinger was interviewed in two sessions for the series, once by a Black non-Jewish producer and once by a white Jewish producer. He was given 20 questions to think about ahead of time, but the first interview, conducted by one producer, turned out to be wide-ranging. Although he is an expert on 20th-century American Jews, the interview began with “let’s talk about 1654,” Dollinger recalled, the year that the first permanent Jewish community was established in the United States with the arrival of 23 refugees from Brazil.

“I was on camera, and she went from 1654, and she walked through American Jewish history up to the contemporary period,” Dollinger said. “I was mentally exhausted by the end of that.”

Then he sat for a second interview with the other producer who began, to Dollinger’s surprise, “What do you think about Donald Trump?”

“I did not have this on my bingo card,” Dollinger told J. “And then [the producer] said, ‘I’m going to start today and go backward in time.’ So we spent the next hour and a half going back to 1654.”

It was at this point that the real thrust of the project became clear to Dollinger. “This is about getting Jews and Blacks back together in political alignment to fight fascism today in America,” he said.

The meat of Dollinger’s interview comes in the third episode, which delves into the heart of what most Jews think of when they think of Black-Jewish relations, the Civil Rights Movement and the so-called Black-Jewish alliance.

He hopes that white Jewish viewers will come away from the series with a more complex understanding of that alliance of the ’60s.

“There’s more to this story than we were raised to think,” Dollinger said. “Knowing more of the story is the path, not only to our own sense of redemption, in terms of understanding our own history, but we cannot enter into a successful alliance and bring social change unless and until we are willing to understand the layers of depth, the complexity of what this alliance was and still is.”