Jury deliberations were underway Monday in the trial of five people charged with breaking into and vandalizing the Stanford University president’s office during a pro-Palestinian protest in June 2024.

Attorneys presented closing arguments on Thursday and Friday.

The defendants, Taylor McCann, 33; Maya Burke, 29; Hunter Taylor-Black, 25; German Gonzalez, 22; and Amy Zhai, 22, all Stanford students and alumni, face two felony charges: conspiracy to trespass with the intent to occupy, and vandalism totaling more than $400 in damages.

Although 11 protesters were indicted in October, six of them received mental health diversions or agreed to guilty pleas on reduced misdemeanor charges.

The witnesses included a 12th protester, who had pleaded no contest, as well as a Stanford police officer and a university facilities director.

None of the defendants took the stand.

John Richardson, the protester who testified, said he was tasked with covering security cameras during the building takeover. Richardson, a student at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles, confirmed the identities of the protesters who entered the building at the time of the protest.

Questioned by defense attorneys about his motives on the day of the protest, Richardson said he “did not feel particularly remorseful” for participating in it.

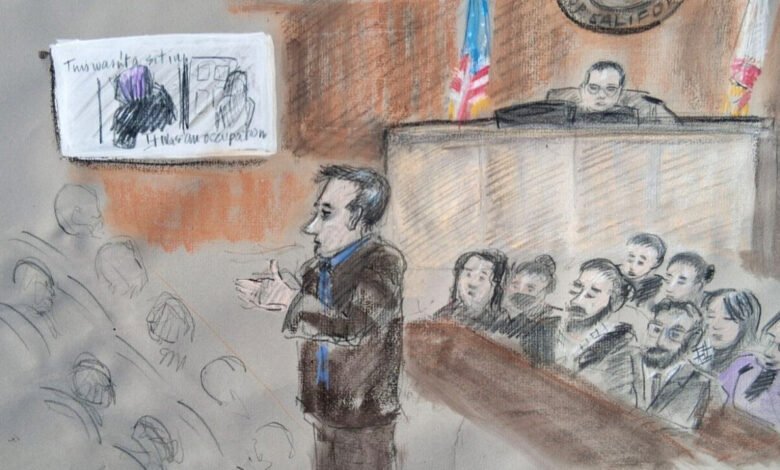

The courtroom was packed with supporters of the defendants at the start of closing arguments Thursday, many wearing kaffiyehs and signs that read “Free the Stanford 11.”

During the trial, prosecutors presented evidence of thousands of dollars worth of damage to Stanford facilities caused by the protesters, arguing that their political motivations were not central to adjudicating their innocence or guilt. For their part, defense lawyers argued that their clients were engaged in a principled act of political protest against what lawyers repeatedly referenced as a genocide in Gaza.

Robert Baker, a Santa Clara County deputy district attorney, addressed the defense team’s political arguments during his closing argument on Thursday.

“A guilty verdict does not mean you support genocide or don’t support Palestinians,” Baker told the jury. “This is not a forum for the jury to express their beliefs on the morality of global warfare.”

He reminded jurors of their responsibility to come to a unanimous verdict based solely on the evidence presented during the case. He strongly advised against discussing their viewpoints of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict or basing a verdict on them.

“The defendants, unlike other protesters, chose to achieve their goals in the wrong way, using actions that violated the laws of the state,” Baker said. Arguing that the defense team was, in his view, using the criminal proceedings for political grandstanding, he added, “This trial is nothing more than an extension of their protest.”

Avanindar Singh, a Santa Clara County deputy public defender representing Gonzalez, disagreed with Baker and challenged any notion that the government “has any say” over what the jury discusses in the deliberation room.

“You decide whether their dissent is criminal,” Singh told the jury.

Leah Gillis, a defense attorney representing Burke, took issue with Baker’s characterization of the defense’s strategy as an extension of the students’ protest, but nevertheless urged the jury not to discount global affairs in its decision.

Baker “is denying the truth of the genocide,” Gillis said in her closing argument. “The jury is not supposed to leave behind what they know to be true in the world. This is government gaslighting.”

Mitchell Bousson, a Stanford facilities director, testified to the costs of the repairs in the building following the early-morning protest on June 5, 2024.

Baker listed some of those costs at the outset of the trial. A bar on one of the exit doors cost $700 to repair, he said; an antique grandfather clock that was sprayed with fake blood cost $10,000 to be professionally assessed and $1,000 to clean; and broken doorframes of two offices each cost $6,000 to repair.

The minimum amount of damage to charge vandalism as a felony in California is $400.

In their closing arguments, defense attorneys claimed that Bousson’s testimony was unreliable because he was unable to confirm the condition of the building prior to the protest. They also pointed to the fact that Baker had no proof that any of the defendants were responsible for the broken window, which allowed one member of the group to enter the building and then let the remaining protesters enter through a nearby door.

In his closing argument, Baker said that the defendants’ presence near the building at the time the window was broken, along with specific methods in the group’s planning documents, sufficiently proved that they aided and abetted the vandalism.

“In this case, vandalism was necessary for the occupation to happen,” Baken said. “There is no legal reason why they would not all be guilty of vandalism.”

Jason Barnes, a patrol officer with the Stanford University Public Safety Department, took the stand early in the trial and was asked to review police body-camera footage in which officers were heard mocking the protesters.

“If you don’t want to get hurt, don’t get arrested b****,” one officer said, referring to Zoe Edelman, one of the protesters who was granted a mental health diversion.

Baker described the defense’s references to the clip as a red herring, saying that it was not directly relevant to the case because Edelman was not a defendant and that the statement was not made in her presence.

In another clip showing officers attempting to take apart the barricade behind one of the building’s doors, one officer says to another that the protesters are “willing to come out one at a time.”

The defense attempted to use this clip as proof that the defendants were not guilty of trespass with the intent to occupy the building for an extended period of time. Baker countered, saying that if the protesters did in fact intend to leave one at a time, they could have done so before police arrived to arrest and remove them.

Anthony Brass, a defense attorney representing Taylor-Black, called the trial a “sham.”

“The penal code is not designed for acts done in furtherance of a humanitarian mission,” Brass said, later making an apparent reference to the September 2024 Mossad operation that used beepers to target leaders of the terrorist group Hezbollah in Lebanon. “The bombs, the tech, the drones, the exploding cellphones — those are funded by Stanford University,” Brass said without providing evidence.

Gillis filed a motion for mistrial on Thursday following Baker’s closing argument, arguing that his remarks to the jury and throughout the trial were “abhorrent.” Santa Clara County Superior Court Judge Hanley Chew denied the motion on Friday.

The maximum penalty for felony conspiracy to trespass and felony vandalism is three years in state prison. But Santa Clara County District Attorney Jeff Rosen previously stated that he would not recommend incarceration. Instead, he suggested they make restitution to Stanford and perform court-ordered cleanup work.

“Dissent is American,” Rosen said at the time. “Vandalism is criminal.”