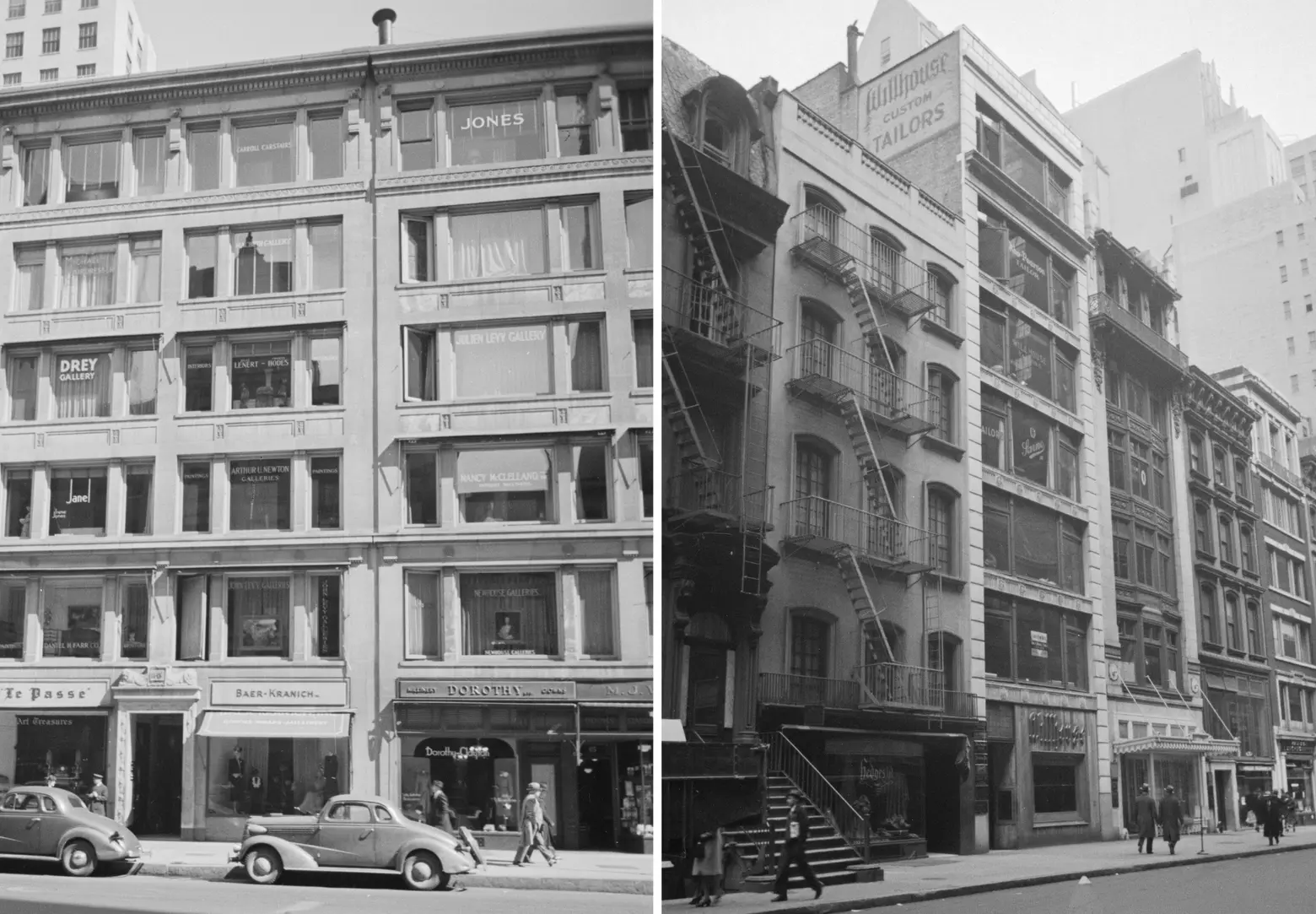

All photos courtesy Municipal Archives, City of New York

In the interwar years in New York City, the cultural epicenter of New York, particularly its art galleries, was centered around 57th Street. One block, in particular, between Fifth and Madison Avenues was the crème de la crème of addresses. Today, the short 450-foot stretch is populated by luxury brands like Tiffany’s, Louis Vuitton, Chanel, Christian Dior, and Burberry. The cluster of art galleries is part of the subject of my new book “The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland,” which covers the flight of Picasso’s art dealer, Paul Rosenberg, and his family to New York City during World War II.

Over the years, the city’s Gilded Age barons had moved more and more uptown. Shopping and culture moved northwards accordingly, first to Ladies Mile around the Flatiron Building and then up Fifth Avenue, where the Vanderbilts migrated to build their opulent mansions. By the 1910s, the city’s elite was eyeing the Upper East Side, and the stately townhomes and mansions on 57th Street began to lose their luster as residential real estate. The properties were snapped up by commercial artistic enterprises and, in some cases, rebuilt taller than before, irking the old guard holdouts on the street.

The first was the Durand-Ruel gallery, the New York City extension of the venerable Parisian gallery, at 12 East 57th Street in 1913. Durand-Ruel had ushered in the Impressionist movement, representing and supporting the likes of Corot, Monet, Renoir, and Pissarro. Carrère and Hastings designed their eight-story French Renaissance-inspired building on 57th Street, with the upper levels serving as the home of the family—a practice that would be repeated on the block.

The Knoedler gallery—later infamous for the forgery scandal—would also commission Carrère and Hastings to build their own five-floor gallery at 14 East 57th Street, which opened in 1925. Also in the 1920s, Frederick Keppell & Company opened at 16 East 57th Street; its owner, who also lived above his new gallery, specialized in etchings and engravings and was affiliated with Modern artists like James McNeil Whistler and Jean-François Millet. Other illustrious art galleries, like Wildenstein and Duveen, were located on the streets immediately surrounding.

When the Museum of Modern Art first opened in rented rooms in the Heckscher Building on 57th Street and Fifth Avenue in 1929, the area attracted a more avant-garde crowd of both buyers and sellers, and in the 1930s and early 1940s, a new wave of art galleries arrived on this block.

In 1937, Curt Valentin, a Jewish emigree, was permitted by Nazi Germany to flee the country with an agreement that he would set up the American arm of the Buccholz Gallery in New York City and send the proceeds back to fund the war effort for the Third Reich. He arrived with a stock of “degenerate art” despised by Hitler that had been seized from German museums.

The Buchholz Gallery was located at 32 East 57th Street. Through Valentin and the Buchholz Gallery, The Museum of Modern Art purchased five paintings from an auction of degenerate art in Lucerne, Switzerland, a scene detailed in “The Art Spy,” in June 1939.

In 1940, Paul Rosenberg, the exclusive dealer to Picasso, Matisse, Braque, and Léger, fled France as the Nazis invaded his country and set up a new life in New York City with the assistance of Alfred Barr, the director of The Museum of Modern Art. Barr had written to the U.S. authorities in support of refugee visas for Rosenberg and his extended family. Rosenberg initially set up his gallery, Paul Rosenberg & Co., inside the Hotel Madison, where he had taken up residence, but found the setup challenging, particularly for potential clients who wanted to see art anonymously without having to announce themselves at the front desk.

Rosenberg landed on the four-story building formerly belonging to the Keppel gallery, spending about $20,000 to renovate it; he believed it was the best address in New York. Following the tradition on the street, the gallery was on the bottom two floors and the Rosenbergs lived on the top two.

Rosenberg decorated the interior himself and was on the lookout for Regency era furniture at a good price. He planned to recreate the feel of his Paris gallery on the ground floor and lobby, and his London gallery on the second floor. He hosted popular exhibitions on the likes of Picasso, Max Weber, Braque, Cézanne, and Renoir, along with benefit shows, including one on Van Gogh for the American Red Cross and another for US Navy relief.

In the decade following World War II, however, the 57th Street gallery cluster changed dramatically. Durand-Ruel closed up shop in 1950. In 1951, the Buccholz Gallery was rechristened the Curt Valentin Gallery but lasted only a few more years due to Valentin’s death in 1954, after which the business was liquidated. Paul Rosenberg relocated his gallery to East 79th Street in 1953, and his daughter Marianne Rosenberg now runs the gallery Rosenberg & Co. at 19 East 66th Street, continuing the tradition of her father and forebears.

New types of business moved in on 57th Street, gradually displacing the art galleries, and by the 1980s, the once venerable mansions that housed the Knoedler, Keppel, Rosenberg, and Durand-Ruel galleries were knocked down to make way for the IBM Building.

In the 2000s, 57th Street underwent an even more unrecognizable rebirth as the address of New York City’s supertalls. A new art district popped up in Chelsea, but a handful of art businesses endure on 57th Street, concentrated between Madison Avenue and Park Avenue, the only remnants of a once-illustrious stretch of art galleries in New York City.

Michelle Young is the author of “The Art Spy: The Extraordinary Untold Tale of WWII Resistance Hero Rose Valland,” now out from HarperOne, and the founder of Untapped New York.

RELATED:

Source link